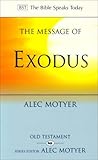

This recent addition to the BST series is another from the respected commentator Alec Motyer. Although, in keeping with the series, this volume does not attempt to be a commentary, it would appear that Motyer would quite like to have written one anyway. The normal flow of the book, which considers the Christian relevance of the message of Exodus is interrupted with regular “Notes” sections (in addition to the standard footnotes), which relate specifically to individual verses, and are much more like the material found in a standard commentary. This can make it a bit disjointed for those reading cover to cover, but will be helpful to those who approach the book as a reference.

This recent addition to the BST series is another from the respected commentator Alec Motyer. Although, in keeping with the series, this volume does not attempt to be a commentary, it would appear that Motyer would quite like to have written one anyway. The normal flow of the book, which considers the Christian relevance of the message of Exodus is interrupted with regular “Notes” sections (in addition to the standard footnotes), which relate specifically to individual verses, and are much more like the material found in a standard commentary. This can make it a bit disjointed for those reading cover to cover, but will be helpful to those who approach the book as a reference.

The main sections of commentary deal with Exodus in moderately sized chunks, drawing out the main theological and practical lessons found there. The book is of course understood in the light of the New Testament, and while Motyer expresses caution about spiritualising interpretation of the closing chapters of the book, generally he is in agreement with the main points that older commentators have detected. Christians are understood as priests under the great high priest Jesus.

The notes sections are more technical, and often refer to the Hebrew, which is always transliterated. Only selected verses are covered in this way, and it also allows extra space for Motyer to highlight the chiastic structures he finds throughout the book. While he does not make a full case against the documentary hypothesis, he takes regular opportunities to show why he feels it is unfounded.

Different portions of Exodus are covered at different speeds, with two thirds of the commentary covering the first 20 chapters of Exodus. Motyer is concerned to highlight aspects of Yahweh’s self-revelation throughout the book, and also to parallel the experience of the Israelites with our own – for example the struggles we face through life are like the wilderness experience.

Many theologically controversial issues are touched upon through the course of the book. For example, issues of free will and God’s sovereignty, the ongoing place of the Ten Commandments in Christian life, what to make of some of the severe punishments meted out, and God’s changing his mind. Motyer’s comments are usually balanced and instructive, without offering full treatments of these subjects.

Overall it is a bit more heavy-going than other BST volumes to read cover to cover, and perhaps Motyer’s work would have been better suited to a more intermediate level commentary series. Having said that, there is a broad range of helpful and practical material here that will benefit those who want fresh insight and deeper understanding of the book of Exodus. As with all BST volumes, the author’s deep reverence for God and respect for his word is evident throughout, alongside a pastoral heart for the readers.